My bookshelf has presented me with several challenges over the years, including but not limited to the dense third part of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot and the entangled, mystifying Buendía family tree in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. Thankfully, no hurdle has been insurmountable thus far, each offering a unique experience within the entertaining, edifying and eternally enlightening realm of classic literature.

Though the same cannot be said of several high school textbooks and non-fictional works, in my 28 years, I have never failed to finish a novel. This is more a testament to my careful selection process than my determination that is notably indefatigable when it comes to reading. Beyond biased blurbs, I tend to choose novels based on their legacy, either as all-time classics or books revered by the artists I admire; the latter criterion naturally conjures the more obscure items.

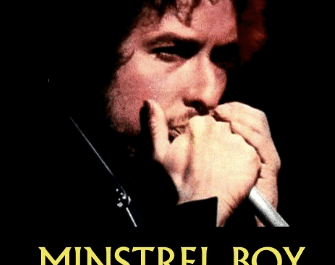

Today, I return to my desk to discuss one such peculiar addition to my shelf: The Bark Tree by Raymond Queneau. This French fancy found its way to my door through somewhat unique circumstances. A year or so ago, I wrote an article in which I listed the songs, books, films and artists that made “life worth living” for the late post-punk pioneer Rowland S Howard. When the musician who rose to prominence alongside Nick Cave in The Birthday Party wasn’t shredding on his iconic white Jaguar, he could often be found absorbed in the heady pages of fiction. Amongst the list of quality media Howard compiled for his fans was The Bark Tree, which he listed as one of his standout reading experiences.

Having inadvertently advertised this book to myself, I scanned the web for some cursory research and to see if I could find a cheap secondhand copy, but The Bark Tree proved bizarrely difficult to find and seemed to have been out of print for half a century. After a little more digging around, I discovered that the French copies, titled Le Chiendent, were more readily available, even on British sites. A frustrated monolinguist, I finally ordered one of the two old UK copies I could find for sale.

My limited grasp of the French language translates Le Chiendent to ‘The Dogtooth’, so how the English language translator settled upon The Bark Tree is beyond me. In forestry, there is a felling cut for forward-leaning trees called the dogtooth, and dogs do bark, though I doubt translators had these tenuous connections in mind. Further to the confusion, I later realised my hunt for the book had been so scantily rewarded because, since the first few editions, the English translations have been titled Witch Grass. The reason for this still escapes me, but I hope you will agree that it adds to the mystique that enshrouds the book.

With my surprisingly plain-looking copy in hand, poised to take on chapter one, I tried to imagine what a so-titled book could contain. Bark is quintessentially associated with trees; it’s a first degree in the bleeding obvious and equivalent to a story entitled ‘The Fur Cat’ or ‘The Scale Fish’, titles implicit of comedy or flaccid drama. Fortunately, the book benefits from a healthy dose of the former, while digging far deeper than the skin it flaunts at face value. Those familiar with Howard’s storied contributions to the musical world in the late 20th and early 21st centuries might understand how he and such a book became joined at the hip.

Musicians and bark-covered trees are ten a penny, but Howard was unique and obscurely thrilling, just like his favourite book. Pursuing this comparison, I found the novel’s nascent steps in the rich line of French existential fiction to align with Howard’s reputation as an intrepid and introspective artist. This perhaps isn’t so apparent in his abstract contributions to The Birthday Party, such as ‘The Dim Locator’, as it is in his later, moodier work as the leader of These Immortal Souls and a solo artist thereafter.

Having formed in Australia, initially as The Boys Next Door, in the late 1970s, The Birthday Party set sail for London, inspired by the city’s rich cultural history and recent flourish in the musical sphere. Not only was the English capital home to the idolised likes of David Bowie and Roxy Music, but also in the development and flourishing of the punk and post-punk waves, which such artists helped to establish. As a post-punk group, The Birthday Party was interested in bringing a more perverse, insincere edge to the macabre tones associated with British contemporaries like Joy Division and The Fall.

Despite some early signs of cult success, Howard and his bandmates soon grew disillusioned with the UK music scene. Supposedly, the New Romantics repelled their comparatively subversive and intentionally repugnant demeanour, and with the exception of Mark E Smith, none of the British cult heroes could quite match their status as junkie pariahs. Following the trail of Bowie and Iggy Pop, The Birthday Party relocated to Berlin, a city whose dark history was not only palpable but still playing out at the time, with the Wall still very much intact.

Berlin was, as expected, a much better fit for The Birthday Party, the hostile architecture and brutal history feeding into their veins and energising Cave’s manic showmanship. In spite of this superficial profile, Joy Division’s Peter Hook once told me of smoke and mirrors at play in the post-punk scene at the time. “The myth is generally just as interesting as the truth,” he said in our 2022 interview. While on tour with The Birthday Party in the early ‘80s, New Order knocked on their tourmates’ door in search of mischief and mayhem. “Where’s the party?” Hook recalled thinking as the door creaked open to a well-lit room sans chaos. “We went in, and they were all sitting around reading their books… I suppose you have to look behind the image”.

The Birthday Party dragged punk’s anarchic gut into the 1980s long after the first wave, as typified by Ramones and Sex Pistols, had crashed. Spearheaded by the likes of Ian Curtis and Robert Smith, the aftershocks turned the outward vexations of crude punk inward towards the soul. With sociopolitics on the back burner, many of our cherished post-punk idols sought to bring a more erudite, introspective edge to proceedings. With The Cure recording ‘Killing an Arab’, inspired by Albert Camus’ The Stranger, and The Fall naming themselves after another of the French philosopher’s novels, it isn’t difficult to see which corner of the library this musical coterie haunted.

Long before Camus or his fellow existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre picked up their pens, René Descartes founded the inwardly-searching arm of French philosophy, coining the timeless phrase, “Cogito, ergo sum,” which translates from Latin, “I think, therefore I am”. This was the “first principle” of Descartes’ philosophy that questioned what it means to exist. Honing in on this sentiment, Sartre published his fictional masterpiece, Nausea, in 1938. Through the lens of troubled protagonist Antoine Roquentin, he tore apart the doors of perception to posit at length that, in a secular world, the conscious mind and the living or inanimate things it perceives are utterly meaningless. Five years earlier, though in a less profoundly dismal fashion, Queneau examined similar themes in The Bark Tree, a lesser-known work that inspired the imminent works of Sartre and Camus.

The quotidian inhale and exhale of urban life is the bread and butter of the existentialist. After all, mundanity is the best medium in which to examine the absurdity of life. The restless minds of Sartre, Camus and Queneau could be transfixed by the daily shuffle of the city streets or, indeed, a nauseating chestnut tree. Philosophers in this sphere attach very little value to anything, or at least attribute the same value to all things. Just as no life can be greater than another, no back street story holds any more or less value than that unfurled on the high street.

Fine art through the early 20th century taught us quite clearly that distinction is found not so much in the subject beheld as in the way it is interpreted. Queneau’s debut novel or antinovel, as it should probably be described, would have been flat and lifeless through a more conventional writer’s lens, but with a healthy share of literary talent, irreverent wit and progressive metaphysical meditation, he exposed shimmers of significance on the vast sea of insignificance that floods and drains from urban spaces day in, day out.

Insignificance is a relative term denoting seemingly unimportant objects and occurrences, such as an upturned waterproof hat in a shop window brimming with water and buoying a rubber duck. In The Bark Tree, this is the unsuspecting observation that dramatically deflects the trajectory of protagonist Etienne Marcel’s life. As he peers through the window, realising he had walked past many times before without noticing the hat, a casual onlooker, amateur philosopher Pierre Le Grand, begins to follow his every move from a Paris cafe; a silhouette in a sea of silhouettes begins to take form as a “flat being”.

From this sliding door moment, the book meanders a tortuous trail of bizarre occurrences, fraught with deception and decadence, that ripple through ordinary lives on the fringes of the French capital. Marcel and Etienne’s paths soon cross, and as the dominoes fall, nooses are tied, mistakes are made, and all eyes turn to a mysterious junkyard door belonging to an old miser, Father Taupe, which may or may not hide a fortune. Like God, Schrödinger’s cat or Prince Hamlet, the fortune may not be, but its impact on greedy mankind is clear for all to see.

Queneau invites readers to his very first literary world in an innovative fashion worthy of a seat among the classics. The opening paragraph, a masterpiece in its own right, heralds a passage of scenes less concerned with destination than journey: a warped reflection of life itself. Like James Joyce before him, the author neglects the traditional narrative structure, instead revelling in modernist snippets of everyday drama, some resolved, some unresolved. This nonlinear style keeps the reader guessing and is juxtaposed with subtly calculated diction.

Discussing his writing style in Barbara Wright’s English translation of The Bark Tree, Queneau opined that a novel is “a little like a sonnet, though it is much more complicated” and heavily constructed. “I don’t expect everyone to do as I do, but that’s the way it is with me,” he added, “I like my characters’ entrances and exits to be very precise. If there are repetitions, they are intentional. That’s how I work. I hope it isn’t obvious. It would be terrible if it were obvious.”

If you enjoy thought-provoking literature and Howard’s haunting melodies, I bet the fortune behind Taupe’s door that you will find a soft spot for The Bark Tree. After this magnificent debut, Queneau went on to co-found the Oulipo literary movement and released several other notable works of fiction, including Zazie dans le métro.

Similar to Howard, Queneau’s legacy makes up for a lack of spreadability with a thick, nourishing dollop for the ardent cult. Though floating fashionably in the fringes of pop consciousness, both Howard and Queneau inspired seismic movements in their respective fields, never afraid to push the vanguard into uncharted territory. Fame and fortune were never the objective for either artist; The Bark Tree and Howard’s discography instead take a visceral dive into the heart of the human experience, inspiring endless reflection on the species’ cognitive breakthrough and the inevitable brush with several sins.